By Thomas O'Shaughnessy.

Reading Time: ~3 minutes.

The transposing of the European Web Accessibility Directive (WAD) from 2016 into Irish law in September 2020 may have marked a turning point in accessible practice in Ireland. This directive targeting more universal access through accessibility standards will have a direct impact on public sector bodies, including educational institutions. In terms of education, the directive can be utilised as an opportunity to further build on Irish legislation supporting students with disabilities by mandating and mainstreaming accessible practice across all educational environments. This more comprehensive approach towards accessible practice is also in line with the Higher Education Authority (HEA) National Plan for Equity of Access to Higher Education, which promotes the mainstreaming of supports in higher education and the reduction of individualised supports.

This practice of accessibility is also embedded within CAST’s UDL framework, a framework designed to improve and enhance teaching and learning for all students, not just particular cohorts. The UDL framework is gaining momentum in Ireland, evidenced by its increasing appearance across Irish educational literature from primary to post-secondary education and into pre-service teacher training (e.g. Hick et al., 2019; Reynor, 2020; National Council for Special Education, 2019; Quirke & McCarthy, 2020). This UDL approach to teaching and learning has also garnered significant support through the National Forum for the Enhancement of Teaching and Learning’s digital badge on Universal Design for Learning (UDL), which is facilitated through the Association for Higher Education Access and Disability (AHEAD).

The current global pandemic has reinforced the need for accessible practice, bringing to the fore concerns over the potential limitations in the current learning environment as pedagogy shifted from face to face (mostly) to full online teaching. Inaccessible content can discriminate against a variety of students. Therefore, in promoting accessible practice, it is essential to explore what systems are already currently available and to identify potential accessible barriers and opportunities associated with these systems. For example, many Virtual Learning Environments (VLE) already have inbuilt accessible features and others support add-ons like Blackboard Ally & Sensus Access which can provide quick solutions to creating accessible content. Moreover, mainstream products including the Office 365 suite provide a range of inbuilt accessible features, from auto captions and accessible checkers to literacy supports such as the immersive reader (a tool now available across several Microsoft applications).

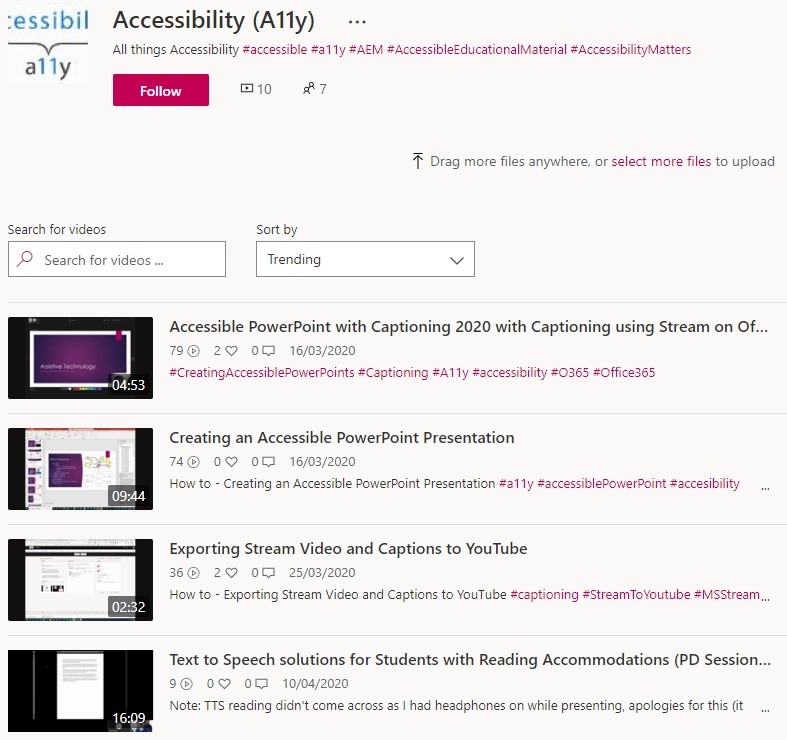

To address concerns over accessibility at the University of Limerick (UL), resources were developed and published through Microsoft Stream. These resources include the university’s Stream Accessible Channel, which highlights a variety of accessible options available to staff, including how to create accessible PowerPoint presentations and Word documents. It also shows how to edit captions in Stream when uploading video content. In addition to these resources, a recorded Continuous Professional Development (CPD) session on accessibility was organized through the Learning Technology Forum (LTF). The LTF, a community of practice dedicated to enhancing digital teaching and learning and representing a variety of educational staff, played an important role in disseminating accessible practice across the campus.

Ireland has witnessed a sharp increase in learners utilising assistive technologies, technologies which often rely on the accessibility of material and services. The recent Irish National Digital Experience Survey (INDEx) highlighted how almost one in ten students believed assistive technology was vital to their learning needs, while 14% of staff claimed to use assistive technology (National Forum for the Enhancement of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education, 2020). These figures further underline the importance of accessible practice in education.

Despite the legal factors (I would argue moral and ethical too), accessibility has encountered some resistance. Concerns over time required to create accessible content and costing are regularly identified as barriers to pursuing accessible practice. Moreover, instructional design encompassing UDL and accessibility from the design phase is one thing; however, retrofitting to support accessible content can be a time-consuming process. Furthermore, the sustainability of universal supports due to financial restrictions can impact how provision is allocated, regardless of any legal or moral issues that necessitate accessible practice. For example, global supports for a captioning service (real-time or human captioned) can incur a significant cost. Edited captions are required because as Parton (2016) notes, auto captions services often lack accuracy. Therefore, legally speaking, auto captions are not suitable for deaf or hard of hearing students. However, accurate captioning has application as a universal tool for all learners. Studies have shown that many learners benefit from this type of support, which has also been shown to increase the retention of international students (Kent, Ellis, Latter & Peaty, 2018; Linder 2016).

The truth is, accessibility, like UDL, is everybody’s business. Legal implications aside, it requires support in the form of a top down, middle out and bottom up approach to become the new ‘norm’ in educational spheres. This also means embedding accessibility in every facet of our educational policy and practice, from procurement to infrastructure and across all learning environments. Ideally, the best time to plan accessibility into your courses is to start working on it before the semester starts. While the task may seem a little daunting at first, perhaps following Tobin & Behling’s (2018) ‘Plus One’ approach and find just one thing that can be added or revised to improve the accessibility of educational content. Remember, the UL Accessibility Channel on MS Stream (which is available to all UL staff) is a great place to start you on your accessibility journey.

References:

Hick, P., Matziari, A., Mintz, J., Ó Murchú, F., Cahill, K., Hall, K., & Solomon, Y. (2019). Initial Teacher Education for Inclusion: Final Report to the National Council for Special Education.

Kent, M., Ellis, K., Latter, N., & Peaty, G. (2018). The case for captioned lectures in Australian higher education. TechTrends, 62(2), 158-165.

Linder, K. (2016). Student uses and perceptions of closed captions and transcripts: Results from a national study. Corvallis, OR.

National Council for Special Education (2019). Policy Advice on Special Schools and Classes: An Inclusive Education for an Inclusive Society? Progress Report. Trim: Co Meath.

National Forum for the Enhancement of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education, (2020). Irish National Digital Experience (INDEx) Survey: Findings from students and staff who teach in higher education, Retrieved from https://www.teachingandlearning.ie/publication/irish-national-digital-experience-index-survey-findings-from-students-and-staff-who-teach-in-higher-education/ [date last accessed: 30 November 2020].

Parton, B. (2016). Video captions for online courses: Do YouTube’s auto-generated captions meet deaf students’ needs?. Journal of Open, Flexible, and Distance Learning, 20 (1), 8-18.

Quirke, M., & McCarthy, P. (2020). A Conceptual Framework of Universal Design for Learning (UDL) for the Irish Further Education and Training Sector. Dublin.

Reynor, E. (2020). Developing Inclusive Education in Ireland: The Case for UDL in Initial Teacher Education. In Gronseth, S. L., & Dalton, E. M., (Eds.) Universal Access Through Inclusive Instructional Design: International Perspectives on UDL, 258. New York: Routledge.

Tobin, T. J., & Behling, K. T. (2018). Reach everyone, teach everyone: Universal design for learning in higher education. West Virginia University Press.